The effects of the completion of the gas pipeline Nord Stream 2 (NS2) from St. Petersburg to Germany through the Baltic Sea will be numerous. The most important of these will involve national security, energy security, geopolitics, European Union (EU) energy policy, and governance, while the gas supply will hardly be impacted and the costs are already sunk—the only question is who will benefit from transit revenues. Numerous countries would be impacted, notably Belarus, Germany, Poland, Russia, and Ukraine, but also Eastern Europe as a whole, the European Union, and the United States. A controversial aspect is the application of US sanctions against subjects in allied countries.

What is Nord Stream 2?

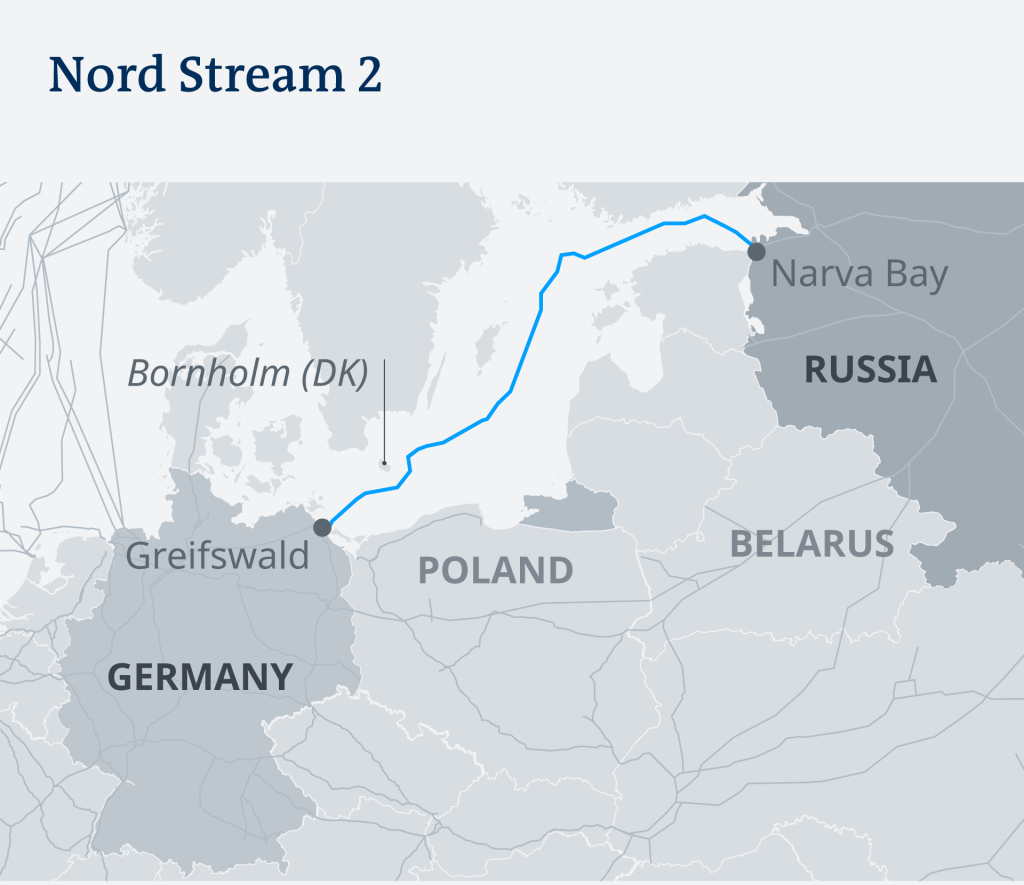

Nord Stream 2 is the second natural gas pipeline running under the Baltic Sea from western Russia to northeastern Germany.

Along with its earlier cousin Nord Stream 1, which opened in 2011, the new pipeline has a transport capacity of 55 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year.

Nord Stream 2 cost €9.5 billion ($10.6 billion) to build and, at 1,230 kilometers long (764 miles), is the longest subsea pipeline in the world. First conceived more than a decade ago, construction began in May 2018 and was completed in September.

However, Nord Stream 2 has yet to begin pumping gas as its operating license has been delayed.

Why Germany needs it so much and how is it affecting the Nato block?

Germany is almost totally reliant on natural gas imports, with Russia accounting for more than half of supplies in 2020, according to IHS Markit. Europe’s number 1 economy is energy transitioning from its reliance on coal and nuclear sources to natural gas and wants to use it as a bridge until it can build or import infrastructure for renewable energies. This urgency has become more visible as Germany has closed three of its total six nuclear power plants last month and plans to shut remaining three by the end of this year. The pipeline belongs to the Russian state-owned company Gazprom and was built with the backing of five European energy firms.

United States role : The United States and allies have fears that Nord Stream 2 would make Europe too reliant on Russian gas, which they say Russian President Vladimir Putin could use as leverage in disputes with the West. USA president biden recently met the royal head of Qatar to discuss possible supply of natural gas to germany in order to shelve down the Nord pipeline project. It is notable here that Qatar has one of world’s biggest natural gas reserves.

Financial implications

The financial effects if NS2 is completed or not will be significant, but not major. They fall into two groups. One group is redistribution of transit fees in the case of completion of NS2. The other is the sunk construction costs of NS2.

Traditionally, Ukraine has made $3 billion a year on transit fees, which have fallen to less than $2 billion a year now that Russia has reduced its transit volumes after having cut its supplies and diverted them to NS1. Poland and Belarus probably each receive transit fees of about $500 million a year, though Gazprom has seized ownership of the pipeline through Belarus. With the completion of NS2, Germany would receive transit fees on the order of $2 billion a year to transport gas to Southern and Eastern European countries that might have been forced to pay slightly more for the Russian gas. There is also a risk that the completion of NS2 will aggravate monopoly effects, about which the European commissioner for competition policy has complained at length.

In December 2019, Gazprom and Naftogaz concluded a five-year agreement on gas transit through Ukraine. Gazprom committed to ship 65 bcm in 2020, and then 40 bcm in 2021 and in each subsequent year until 2024.16 Gazprom complied with its contracted obligations in 2020, but it had a commercial interest in doing so. Given Gazprom’s record of patently breaking its agreements, this is no reassurance. Nor is Gazprom able to provide any credible guarantee.

In 1997, Gazprom suffered from a surplus of gas. Then, it stopped accepting any gas supplies or transit from Turkmenistan for one and a half years, while Turkmenistan had no other outlet. Russia ended its blockade only after Turkmenistan had built an alternative pipeline to Iran. In the spring of 2009, gas was plentiful again. This time Turkmenistan’s pipeline to Russia “accidentally” blew up because Gazprom stopped taking Turkmenistan’s contracted gas without informing Turkmenistan.17 The President of Turkmenistan learned his lesson. Now, China has built a large pipeline to Turkmenistan, so that it does not have to rely upon Russia any longer.

Why wouldn’t Gazprom do the same to Ukraine? The operation of the transit pipeline requires a reasonably steady flow, which Russia never provides. Gazprom could stop for half a year, which would stop the gas transit from functioning, and then complain that Ukraine does not fulfill its contract obligations. Considering that Gazprom regularly loses multi-billion-dollar arbitration conflicts in Stockholm, Gazprom cannot be trusted.

Because of various legal intricacies, Gazprom was forced to take full ownership of NS2. It was supposed to cost about €9.5 billion, but is probably closer to €11 billion. Gazprom is supposed to finance half of NS2 on its own, while its five Western partner companies are supposed to lend €950 million each to the project.18 The big legal question is who, if anybody, becomes liable if the project is stopped. If US sanctions stop it, as currently seems likely, nobody is likely to be held responsible, because so far nobody has managed to successfully sue the US Treasury Department over sanctions. If the German government stops the project, it might become liable, since it has previously approved of NS2. A third option is that the European Union, in one of its many forms, blocks the project. It is unlikely that the EU would be liable, as it has never really approved of NS2 but was overrun by the German government.

~ sahil khatri , prospective business majors (finance) and physical sciences graduate